The more you read about the Options Scandal the more complicated it gets. So let's try breaking it down with the help of Network Appliance CEO, Daniel Warmenhoven, using

this interview with Businessweek's Peter Burrows.

I think the government is looking to... publicly hang people... That's fine. But where does it stop? I'm not saying the past practices were all good. But I thought the SEC's role was to build investor confidence. What they're doing right now is destroying it, and I don't see the purpose. They're penalizing today's shareholders for events that occurred five years ago. But who is this protecting, exactly? With Enron, every shareholder in the company lost money. The same with Qwest, and with MCI-Worldcom. But I don't know who the injured party is here.

Mmmm Hmmm....

Probably for sake of brevity, Peter Burrows doesn't point out it's actually the CEO/Board of Directors who are responsible for investor confidence. Instead, he just kindly explains that investors didn't get the same sort of special deal available to insiders. Then he lets loose an open-ender, wondering why are so many companies in so much trouble?

This is going to sound weird, but what difference did it make [if the options expense was recorded on company's official financial records using generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP]? It was going to be removed for the pro forma reports anyway, and that's all the investment community cared about. And there was no rigor around the enforcement of this [by the SEC]. I'm not trying to defend the practice. But [properly disclosing and expensing in-the-money options] just wasn't viewed as a high priority by anyone. It generally wasn't even audited by the audit firms. The view was that close enough is close enough, which is why some people crossed over the line.

Alrighty then.

As you know, you have to be really smart to get a job with Businessweek, and Peter is a good example of that. So he ain't done with this fella by a longshot. Later in the interview he tricks Mr. Warmenhoven, wondering what a CEO could do to protect shareholders.

There was a lot more focus on the number of shares we granted than on the price.The number of shares is what creates dilution, and we manage the number of shares being granted every year within a dilution cap. Every year, I talked to my big shareholders and asked for their support [for the year's options program], and explained to them in great detail what the options will be used for...

Yyyyyeah...

OK, so probably not the best person to explain the industry's perspective afterall (by the way, in case you don't have time to read the whole interview, he continues by describing the ways regular people like us are speeding and nobody does anything to stop that either).

All kidding aside, this scandal rubs people the wrong way because the whole point is simple fairness and responsibility.

And this is

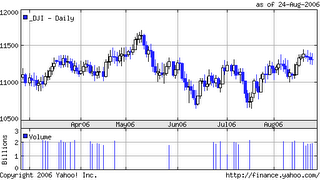

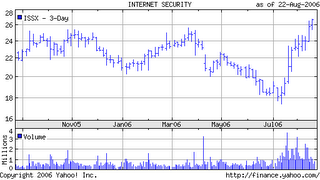

not a question about what the market will bear. You'll never see me complain that Cisco's

John Chambers gets $149,000 per day from his totally legal and publicly disclosed options contracts...

even though the stock has gone nowhere for 8 years. (I should point out it's not a real market when you and a few of your golfing buddies sit around the table and just make stuff up.)

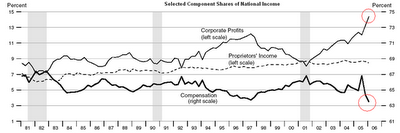

But honestly, the real reason for this rant is not about the options scandal, per se. The big revelation here can be found if you direct your attention to the humongous investors Mr. Warmenhoven checks with for legal and accounting advice.

Turns out you've apparently got the blind leading the blind, because those institutions are a bunch of morons.

Witness: while a lot of these big institutional shareholders have been keeping track of those "dilution caps", with a wink and a nod, their option-happy CEO's have been shoveling the company's cash into stock buybacks. (Note: Cisco apparently had a different approach: they are spending some $40 Billion after years and years of dilution.)

At the same time those CEO's and other insiders have been selling stock all the way down (that's the beauty of options awards: it's all relative. If a stock goes south, from, oh I don't know, say, $150/share to $5... before getting back to $32 and change, you just keep getting new awards with lower and lower strikes-- a good deal whether or not there's a "look back").

Having said all that, here's why I don't get too upset about such things: eventually the other investors in those aforementioned BIG INSTITUTIONAL FUNDS will take their money away, and in turn Adam Smith's invisible hand sweeps away the greedy CEO and their lazy Board of Directors.

UPDATE (AUG 21):

An editorial in Sunday's tech friendly San Jose Mercury News,

Reality of stock-option drama is most errors were unintended, picks up on the theme that the options scandal is not much more than bookkeeping errors.

Yet still missing from very nearly every piece of analysis is the issue of favorable treatment granted to insiders vs the existing owners of the company.

Put another way, even if it's technically legal, was it fair and responsible?

Before you answer, think about this: can you imagine the shelf life of a systemic, industry-wide bookkeeping error that screwed executives and/or new hires of said companies?